by Megan Brookhouser

August 4, 1985 was an unremarkable date for many Americans. A normal summer day in the nation’s capital, in other words, scorching hot. However, amid the heat, some 15,000 men, women, and children created a 15-mile chain of banners threading through the tourists and politicians going about their day. The members of the chain knew the significance of the date, for it was the 40th anniversary of the United States dropping the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. With it, destroying thousands of civilian lives, decimating entire cities, and wiping away the natural beauty of the land. An event should never have happened, and should never be repeated. That is what these peaceful protesters were advocating through their contributions of time, money, and, most importantly, fabric to the grassroots project simply entitled, “The Ribbon.”

The brainchild of a Colorado grandmother, Justine Merritt, The Ribbon was meant to send a message of peace in an era brimming with the constant threat of violence. Several years before the actual event, Merritt mailed letters to 100 of her closest friends. The pamphlets explained her idea for a nationwide demonstration of peace. She asked each individual to create an 18 x 36-inch banner depicting the things that each person could not “bear to think of as lost forever in a nuclear war.” Each banner was to include small ribbons sewn to all four corners in order to tie the finished products together. Merritt hoped to receive enough banners to surround the entire Pentagon. The mission spread rapidly throughout the nation.

The idea was especially popular with women’s religious groups. It utilized a stereotype in a productive way, giving old church ladies a purpose for their sewing circles. Bible schools, religious orders, and community organizations joined the cause, creating unique banners through every artistic medium imaginable. Dedicated women created intricate images of needlework. School children painted watercolor landscapes. Each banner contributed a new perspective on the beauty of the world.

As the project grew in popularity, it gained structure. State chairmen were appointed to recruit new participants and collect all the banners at the appropriate time. Rev. Sharee Kelly, a pastor from Loup City, took on the position of Nebraska’s state chairman. With her help, Nebraska contributed an impressive 350 banners to the demonstration in Washington D.C. With the slogan “sew to speak,” Kelly garnered support all across the state. She hosted a Ribbon Dedication Ceremony on July 21, 1985 at St. Josaphat’s Catholic Church in Loup City, NE. Following the dedication, the banners traveled to Lincoln, NE for a state-wide peace demonstration and Ribbon Ceremony on July 24. Governor Bob Kerry presided over the event, contributing his own banner to the chain with the handwritten quote, “We cannot make peace with or as machines.” As the ribbon surrounded the state capitol, Kerry proclaimed August 4th National Peace Day. The next stop for Nebraska’s banners was the nation’s capital.

Around forty-two Nebraskans make the trip to Washington D.C. for the culminating ribbon ceremony. Local churches volunteered to host out-of-town participants and Nebraskans were generously taken in by Calvary Baptist Church. On August 3, all the project’s participants gathered for a religious service at the National Cathedral. The non-denominational service featured two guests of honor: Fumimaro Maruoka of Hiroshima and Teru Morrimoto of Nagasaki. They spoke of their experiences as survivors of the bombings and of their hope for a peaceful future. Their moving testimonies stayed in the participants’ minds that next day as they prepared for the long-awaited demonstration.

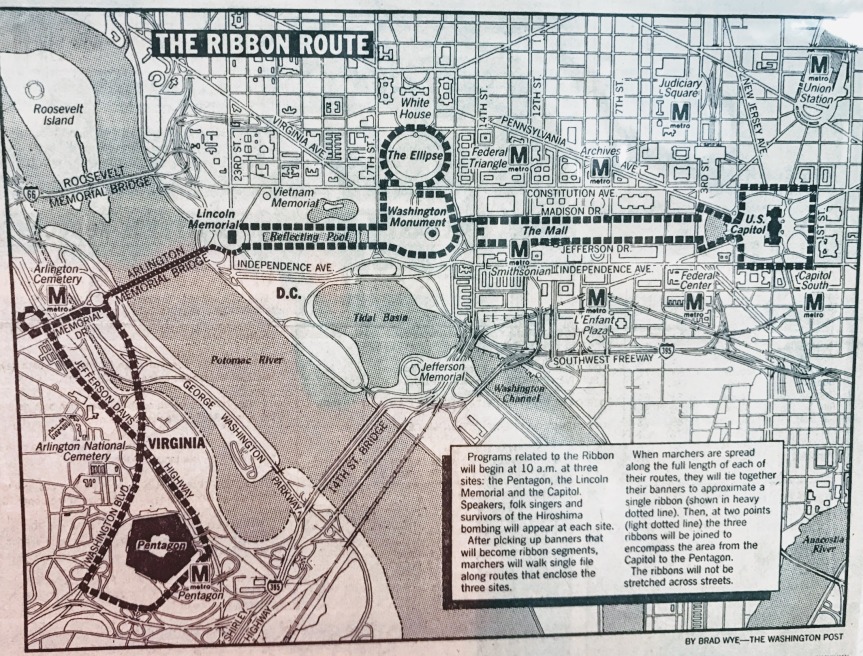

The demonstration was an international effort. The ribbon included banners from twenty different countries, including a 130-foot long section sent from the Soviet Union. It took about 3 hours for the 25,500 panels to be tied together. They stretched for 15 miles. Far exceeding Justine Merritt’s expectations, the ribbon strung from the west steps of the Capitol, to the Lincoln Memorial, and around the Pentagon. The impressive display stopped traffic for several minutes as it crossed the Potomac. Nebraska’s banners generally hovered around the Lincoln Memorial. When the final banner, Justine Merritt’s own, successfully connected the ribbon, balloons were released from the steps of the memorial.

The Ribbon effort deserves more recognition than it has received. Few people today even know of the event. However, in a time of protests for gender equality and peaceful law enforcement, The Ribbon is unbelievably relevant. These elderly church ladies used their talents and their stereotypes to their advantage. They created an amazing display of international solidarity and exhibited the power of a peaceful demonstration. The program for the National Ribbon Ceremony included a quote from Albert Einstein, saying, “We shall require a substantially new manner of thinking if mankind is to survive.” While this is true for many reasons, I believe that recognizing and remembering the significance of a date like August 4, 1985 is a good starting point for this new manner of thought.

The Nebraska ribbons are cataloged at the Nebraska State Historical Society.